A Clockwork Orange got deep under my skin. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a film that’s made me so uncomfortable, and I could point to a variety of things within the movie that accomplished in eliciting that feeling, from the graphic rape scene in the beginning to the Ludovico treatment. But I think what’s truly disturbing about A Clockwork Orange is how, through the point of view of Alex DeLarge, we are made to both loathe and yet pity Alex.

In A Clockwork Orange, Stanley Kubrick uses numerous cinematic techniques to position Alex as part of a larger picture. The opening scene starts with a close-up of Alex staring malevolently into the camera, but as the camera zooms out to cover the rest of the nightclub, more variables and characters are introduced to ground him within a larger context. Alex is sex-crazed and abnormally violent, but the Droogs are not the only violent gang in London, and almost every character has some display of visual pornography on their walls. Alex is an intimidating and abusive leader, but the government subjects a large number of juvenile delinquents to torturous imprisonment. Even though the protagonist is a detestable character, the rest of the film’s society is detestable as well. This brought up the question: is Alex solely responsible for his own actions, or is Alex just a byproduct of the society in which he lives? And if the latter is true, is society just as bad as Alex?

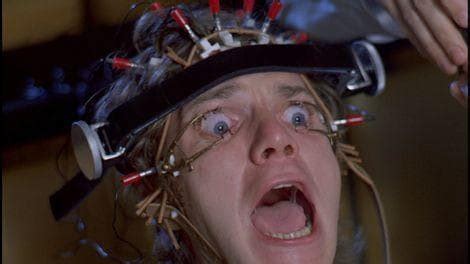

I think a large part of the reason why this question persists is how Alex is painted as essentially unreachable. Fraser mentions this quite frequently in “Ambivalences,” to the point where he connects the unreachable-ness of a violent character to several nihilistic philosophers. According to Fraser, behind every unreachable character lies an unreachable organization, and behind every unreachable organization is “a philosophical nihilism which it is peculiarly tempting for a good many people to see not simply as one philosophical position among a number of others, but as a revelation to use of the truth of the human condition,” (Fraser 23). The final scene of the movie crystalizes this point to perfection; despite everything that he’s been through, from undergoing a horrific psychological experiment to nearly drowning at the hands of his former friends to attempting to kill himself, Alex is still the unhinged monster that we met at the start. In the end, reform is just a performance Alex puts on to persuade others that he is a changed man. This drastically contradicts traditional narrative structure, which predicates that a character ends up in a different state than they were in the story’s beginning. As Alex fantasizes about having sex with a woman in front of an audience dressed in 19th century clothing, his statement of “I’m cured, all right!” is a perfect encapsulation of the nihilism Fraser discussed. For all of society’s efforts to “cure” him of his violent tendencies, Alex is the same person that he’s always been. On one hand, this is a disturbing end to a truly twisted story, as the rapist and murderer has learned nothing. But on the other hand, there is a sense of depraved optimism in Alex’s statement. For everything that society threw at him, he is nevertheless the master of his own free will, and nothing can change him. As discomforting as it is, Kubrick’s interpretation of the source material tells a deeply radical tale of humanity and free will, where even the most depraved members of society deserve to have at least some freedom.

This article was originally written for MS140 PO-01 Screening Violence, taught at Pomona College by Prof. Kevin Wynter.

Leave a comment