Invasion U.S.A. might be one of the most ridiculous movies I’ve ever seen, but it was also ironically one of the most fun. There was something invigorating about what I was seeing onscreen, even though I knew it would be incredibly dangerous and traumatizing in real life. Although it wasn’t as stylish as Natural Born Killers, the style in Invasion U.S.A. was enough to sugarcoat the violence and make it almost commercialized. As I was watching, I got the sense that a kid could ask for a Matt Hunter action figurine for Christmas, and his parents would get them one immediately. Overall, the grandiose aestheticization of the violence in the film works to showcase the film’s ugly freedoms: although one must commit violence, if it is in the name of securing freedom, then it is inherently beautiful.

The introduction to “Ugly Freedoms” really stuck out to me. Freedom is often described as something that is hard to obtain, but as something that should never be taken for granted. If anything, freedom is akin to a shiny and expensive jewel: something that probably came from blood, but is so valuable that it would be traitorous to disregard it. But I was surprised how the author mentioned how historically, ugly freedoms have been justified in the name of aesthetic beauty, especially regarding which bodies are disposable. For example, during the era of the Ugly Laws, which were meant to bar any poor or disabled people from inhabiting public space, the theory that “instantiating public freedom by refusing access to and practicing violence upon bodies deemed unworthy, while also denying those bodies political legibility” (Anker 7) was seen as legitimate. While it may fall under heavy fire in today’s era, the aesthetic justification of ugly freedom is seen heavily in Invasion U.S.A.

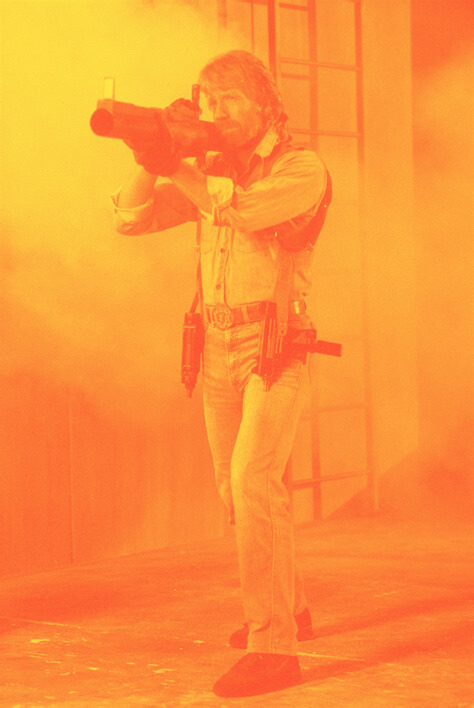

The fact that the film takes place during Christmastime was something that at first caught me off guard, but made sense in context once I thought about it. Christmas is marketed as a quintessentially American holiday, with an air of innocence and gallantry about. When the communist soldiers start invading Florida and wreaking havoc, they target explicitly wholesome landmarks, like the busy shopping mall and a quiet suburb, with the latter being the site of a grandiose bazooka attack. The stark juxtaposition between these wholesome locations and the gruesome violence inflicted upon them amplifies the whole ordeal, much like how shooting a dog is seen as a major step worse than shooting a person. Therefore, when Hunter arrives on the scene and kills all the bad guys, there is a sense of beauty being restored. Despite the fact that Hunter is no better than the communists at violence, the fact that he does it so nonchalantly makes it seem as if it is just common sense to protect the American beauty that is freedom. Considering how Hunter is portrayed as an American “common man,” there is also a sense that every American should be primed to feel this way towards ugly freedoms, although whether the film was trying to commit towards a political ideology or not remains to be seen. For me, the film’s aestheticization of ugly freedoms and violence was accomplished incredibly well. From the fact that there were very little attempts to empathize with the communists to how the film made the protagonist unabashedly cool, there was this overwhelming sense of contagion from how the film wanted you to see the violence onscreen: beautiful.

This article was originally written for MS140 PO-01 Screening Violence, taught at Pomona College by Prof. Kevin Wynter.

Leave a comment