When it comes to imperialism, it normally boils down to a few images. Tanks rolling

over flattened cities. Flames engulfing fertile forests. Soldiers planting down their nation’s flag after they have successfully won a battle. These images almost always accompany a nation’s creation of gendered identity, which is almost always masculine and visible. But there is lesser focus on how femininity is presented during times of warfare, especially when it concerns women’s involvement. Most would assume that women would take on more domestic labor, and in fact many nations paint women working as empowering the nation, with the assurance that they will be back “in the kitchen” after the war is won. But women were not just working from home; in some countries they were helping to protect their countries in the battlefield, but their methods and motivations of doing so were not always clear cut.

In Princess Mononoke (1994), Lady Eboshi and San stand out as figures who embody most of the mentioned traits. Strong, confident, and with massive artillery, Eboshi is the noble leader of Iron Town, a small community that serves as a sanctuary for former sex workers and disabled men, whom Eboshi seeks to liberate from the tyrannical Lord Asano. Likewise, San is a human child adopted by the wolf goddess Moro who has developed a hatred for humanity for their relentless destruction of the forest. Instead of the film presenting one side as clearly right and the other as clearly wrong, both female characters have distinctive flaws, which makes for a far more interesting depiction of gender in a genre that has been historically male-dominated. Although they both present feminine traits such as protectiveness and nurturing, both characters’ aptitude for violence and warfare complicates the picture of feminism of women as more competent and rational leaders than men. In this essay, I will argue that both Lady Eboshi and San represent different types of feminist expression that are reflective of the societies to which they belong. For Lady Eboshi, her protective attitude is reflective of a gendered presentation of leadership that uses feminine language to justify imperial expansion into indigenous lands. But for San, her masculine approach to combat hides a more visceral emotional vulnerability that is a direct result of her precarious position in a hostile, unpredictable world.

Gender & The Military

First, an examination of how gender performance can manifest in warfare is necessary to ground the paper’s analysis. While women have often been portrayed in wartime narratives as domestic laborers such as nurses, a surprising number of women throughout history have been on the front lines fighting alongside men. For example, the book Women at War in the Borderlands of the Early American Northeast America (2018) by Gina M. Martino describes in detail how governments in 17th century New England conscripted women to help fight back against Indigenous communities from the security of fortified buildings. This was done not only to strengthen manpower during times of heavy warfare, but also the community, meaning that a woman’s work was not only for the good of her family, but for the overall collective. This often meant a blurring of gender boundaries. For example, a 1675 judicial ruling by the Massachusetts General Court mandated that all families take shelter in fortified bases, leading to an increased involvement of women in the public sphere. Not only did this change patriarchal family dynamics during this period, but “it also placed women in situations that would demand their assumption of more violent martial roles as public actors, blurring distinctions between the formal and informal public spheres in fortified communities,” (Martino 26). Although systems of power were still overwhelmingly centered around men, women were still considered valuable resources to rely on.

However, this New England system of women fighting for their communities came with troubling consequences for neighboring Indigenous communities. Throughout history, whenever prominent white women have explored uncharted territory around the world, they have often done so while upholding systems that would bring harm onto other communities. Cynthia Enloe points out this phenomenon in her book Bananas, Beaches, and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Relations (2014), examining how the influence of women in international relations in history has gone unnoticed, especially when it comes to colonial efforts to take control of indigenous land. Mary Kingsley is cited as one of the most egregious examples of this, as her exploration of Africa often entailed taking on masculine and feminine characteristics that would have far-reaching implications. Enloe cites how “Masculinity and exploration had been as tightly woven together as masculinity and soldiering. These audacious women challenged that ideological assumption, but they have left us with a bundle of contradictions…in some respects they seem conventional,” (Enloe 33). It is interesting that although a woman taking on masculine characteristics has been seen as a historical positive for women’s liberation, the deliberate ignorance of other societal factors has often meant that white women’s contributions towards colonialism have often gone unchecked.

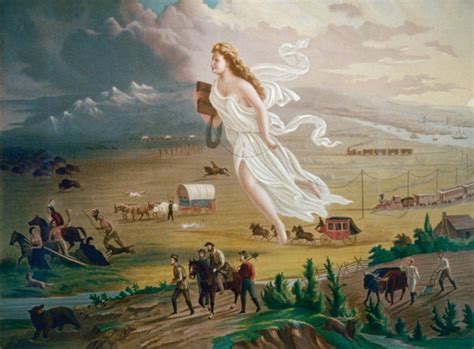

The intersectionality between whiteness and femininity has often been used to perpetuate harmful stereotypes towards Indigenous communities as barbaric and savage, and the destruction of such communities has often been a sign of progress associated with white women’s advancement. In John Gast’s 1872 painting American Progress, the white Lady Columbia is portrayed as an illuminating presence of enlightenment and progress heading towards Indigenous Americans, who are shrouded in darkness. The painting is an apt symbolic representation of the concept of “manifest destiny,” which assumes that Western colonialism and progress is inevitable and that the conquering of Indigenous communities is therefore necessary. Gast worked with publisher George Crofutt on American Progress, and when Crofutt described the painting in his magazine Crofutt’s Western World, there are some intriguing implications. According to Crofutt, Columbia is a “beautiful and charming female…floating westward through the air, bearing on her forehead the ‘Star of Empire,’” (Autry). Columbia represents the more masculine traits of industrialized capitalism and linear progress, but she is also presented as a benevolent goddess, guiding the Western people on their predetermined “destiny”. When white women like Mary Kingsley explored vast landscapes like that of Africa, their positionality carried a sense that once they have reached the land, the colonial progress of Western civilization has reached that community. As opposed to male colonial officers bulldozing forests and killing off marginalized communities, white women have often carried an assumed “civility,” a point of intersection where their femininity and whiteness combine to create a sense of formality and order in the process of colonialism. Due to this characterization, white women have often held contentious positions of power where they are simultaneously fighting one system while supporting another.

In Princess Mononoke, Lady Eboshi’s gendered style of leadership entails feminine characterizations of compassion and restraint, but she also demonstrates masculine traits that reinforce industrialized imperialism. When Eboshi properly introduces herself to Ashitaka, she inspects the bullet the Emishi prince found in Nago’s side and proclaims that it was her who fired the bullet, speaking in a calm, restrained voice. But when she reminisces about how she destroyed Nago’s forest and annihilated most of the boar clan, the flashbacks show her brandishing muskets with her army, and her looking over the burning forest like a conqueror. This juxtaposition between how she is in private versus her public displays of power is troubling, but it is not entirely unrealistic for how a lot of female leaders perform their gender in the international political sphere. Not only does she share similarities with Mary Kingsley’s imperialist doctrine, but she also shares characteristics with another prominent woman in politics: Hillary Clinton.

Much like the former Secretary of State, Eboshi’s language indicates a gendered divide between public and private space that is often the main battleground for women in politics. Many feminist scholars have found disparities in how voters and other politicians view women; they must be firm and strong to present themselves as competent, while presenting a warm feminine exterior to reassure others of their non-threatening veneer. Jennifer Jones wrote an article on how these paradigms impacted Hillary Clinton’s election against Barack Obama from 2007-2008, focusing on how her gendered speech differed based on whether she was in an interview or on a debate stage. Jones found linguistic styles that largely aligned with how people saw male and female leaders. Feminine linguistic styles often reference first-person singular pronouns (“anyone,” “she,” “this,” “your,” etc.) and emotional words, such as “brave,” “cried,” and “disagreed,” whereas masculine linguistics were more forceful, focusing more on first-personal plural pronouns such as “our” and “ourselves” and words that described anger such as “annoyed” and “cruel,” (Jones 631). Jones then constructed a ratio that took the number of times feminine linguistic styles were used and divided them by the number of times masculine styles were used and charted how those ratios changed as the 2008 presidential election progressed. Over time, as the campaign against Barack Obama escalated, the ratio between feminine and masculine linguistic styles decreased, showing that “it is not clear that Clinton’s language was decreasingly feminine, but it is clear that her language was increasingly masculine,” (633). This was especially apparent when Clinton appeared on interviews and debates. While she tended to use more feminine styles of speaking in interviews, which occurred in mostly private settings, in debates, Clinton spoke more assertively, portraying herself in a more masculine way to demonstrate her strength.

Although she is the primary antagonist of the film, Eboshi’s gendered style of speaking entails a strategy to survive and negotiate around a system of power where she is simultaneously the victim and the violator. Her most valuable asset is Iron Town, where she rules as a benevolent leader looking over the former sex workers and disabled men she rescued from destitution. But due to the geopolitical position of Iron Town, the threat of attacks from feudal lords and San means she must secure the adoration of her people while making allyships with untrustworthy men who are a little too quick to pull the trigger, requiring her to walk a fine tightrope of gender performance. She must secure the future of Iron Town, but must rely on the superficial bonds of hunters to do so, and even when things get progressively worse for the women in Iron Town, she must continue to perform masculinity to secure a more long-term future for her village. Instead of masculine traits leading to Eboshi’s empowerment, they put her in a binding situation from which she cannot escape.

San & Femininity in the Wild

However, Eboshi’s struggles are not too distant from San’s, regardless of the wide berth of their circumstances. Whereas Eboshi is a noble lady with a vast array of material resources and political allies, San is a human girl who was quite literally raised by wolves. As a result, when she enters the story, she presents herself as a radical alternative to Eboshi with regards to feminine expression in politics. When Ashitaka first encounters San, he reverently asks if she is of the ancient gods along with the Wolf Clan. Even though she tells him to leave the forest, she squints at him, as if to determine whether his true motives. It is also a sign of genuine interest; despite her hatred towards humans, San is nevertheless curious to find a human that does not see her as a natural enemy. This is where the products of her upbringing are most apparent. Very little is revealed about her backstory: her adoptive mother Moro tells Ashitaka that her parents abandoned her in the forest when she was a baby and since then San has grown up to look at the wolves as part of her family. As a result, San does not only detest humans for abandoning her,but she also hates them for threatening to destroy the habitat where her adoptive family lives, along with other animal tribes that have been put at risk.

The mountainous forest San lives in means she is positioned directly above Iron Town, making her worldview predominately shaped by her experience in physical exile. Exile, widely seen as a sign of political alienation, has actually shown to reap some profit for marginalized groups under threat from oppressive states. In southeast Asia, there is a transnational community called Zomia, which consists of many nomadic tribes who want to exist outside of statehood, where they will be at definite risk of subjugation and loss of culture. James C. Scott, the author of The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Southeast Asia (2009), points out how living in the mountains is a huge advantage for these tribes, because it provides them with a fluid culture and physical distance away from harmful state systems that rely on manpower to survive. Scott highlights how the European state system managed to bring in many rebellious tribes through their rigid power structures, which meant that the state could hold some leaders hostage to gain some sort of leverage over the less powerful tribes. But while tribes in European history had structure to them, this is less so in Zomia. Scott cites the term “jellyfish tribes” by Malcolm Yapp to describe these structures, and says “it points to the fact that such disaggregation leaves a potential ruler facing an amorphous, unstructured population with no point of entry or leverage,” (Scott 210). Although San’s adherence to the Deer God does provide some semblance of structure to her life, at the end of the day all she has is her wolf family, who will protect her no matter what. In a sense, San is less than a primary leader of an establishment and more of an intermediary figure, negotiating between the forest at large and the human world. But even though she is not an outright leader of a community like Eboshi, the position of an intermediary can exact just as heavy a toll, especially with her regards to how her rage manifests in her combat.

Although she never declares herself as such, the people of Iron Town refer to her as “Princess Mononoke” (or Mononoke-hime in Japanese), which is strange, because San never refers to herself that way. But the fact that the people of Iron Town refer to her as a vengeful spirit in Japanese indicates something integral about her character; her volatile emotional state reflects a harsh reality about female leadership in an unpredictable landscape. Throughout the film, San’s avid protectiveness of her wolf family is reminiscent of the protective attitude of 17th century New England women, to the point that the very existence of Iron Town represents an existential threat to her way of living. Due to her status as an intermediary figure, there is only so much she can do to protect her family. No matter how hard she tries to fight Eboshi, the sheer firepower the latter has easily destroys the forest. In a sense, her vengeful approach to combat acts to compensate against her relative insignificance, which makes her hug with Ashitaka in the climax of the film so powerful.

When the apes confront San after Ashitaka rescues her earlier in the film, they derisively tell her she is nothing more than a human, and not a wolf as she claims to be. This strikes a nerve for her, but when Ashitaka hugs her after the Deer God is killed, he tells her that she is a human too, and that since they are both human, they can work to revive the spirit together. The reason why this is such a cathartic moment is that San no longer sees herself as a nigh-invulnerable spirit, but rather as a girl who was struggling her entire life to belong. Her guiding motivation in the film was to protect the forest and her family, but the existential threat posed by Eboshi and Iron Town pushed her protective instincts to the limit. For all her masculine combative skills, there was only so much she could do to defend the forest, and the death of the Deer God forced her to confront this hard-to-swallow truth. Ashitaka’s hug with her in the climax is the epitome of this; only when she is at her most vulnerable was she able to realize that there was still something she could do. Unlike most female leaders in politics, her embrace of her femininity at this pivotal moment allowed her to overcome the odds through a shared recognition of humanity, rather than using a front in public.

The main strength of Princess Mononoke is not only the presence of two complex female leads, but also in how they are morally presented. Neither is good or evil; while one seeks the destruction of the other, the viewer can understand where they are coming from, and how their respective structures influenced their outlooks. In some ways, one could argue they are two sides of the same coin. For Eboshi, her noble background granted her agency to look after vulnerable people, but her appeals to military force ultimately doomed the quest she embarked upon. In contrast, San’s stateless upbringing made her into a fiercely combative individual who knew how to navigate chaotic lands, but at the cost of her own emotional security amidst rising turmoil. By the end of the film, both characters realize that although they are powerful in their own right, they are insignificant compared to the raw power of the environment to wreak havoc on humanity. Their character arcs also have implications for gendered leadership in international relations. Instead of forcing prominent women to adopt masculine traits to dominate over others and perpetuate harmful systems in the name of female liberation, world leaders should seek to look for alternative solutions that do not involve warfare, seeking to understand the other person’s perspective and any power imbalances that might come into play. This would especially help women around the world, who are often the most directly affected by warfare and unrestrained global conquest. In Princess Mononoke, Hayao Miyazaki did not just write a fantastic story about sword-swinging women; he also wrote a story about how vulnerability can help win wars.

Works Cited

Collections, Autry. “Autry’s Collections Online — Painting American Progress.” The Autry’s Collections Online, 2024.

Enloe, Cynthia H. Bananas, Beaches and Bases : Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. Second edition, University of California Press, 2014.

Jones, Jennifer J. “Talk “Like a Man”: The Linguistic Styles of Hillary Clinton, 1992-2013.” Perspectives on Politics, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 625–42.

Martino, Gina M. “Women at War in the Borderlands of the Early American Northeast.” University Press Scholarship Online Complete Collection, University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Scott, James C. The Art of Not Being Governed : An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Yale University Press, 2009.

This article was originally written for POLI181 PO-01 Ghibli and Foundations of Poli Sci, taught at Pomona College by Prof. Thom Le.

Leave a comment