In this genre-shifting thriller, a manhunt for a dangerous extortionist leads the audience through the most divided parts of Japan in Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 picture.

There’s a house up on a hill. Its minimalist, with a panoramic view of the city that lies below. At the bottom of the hill lies a studio apartment that barely fits two people, and someone plans. While the house on the top can see everything like a king, the people below are gazed upon by the giant house, like the god-like billboard of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg from The Great Gatsby.

In Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 film High and Low, the person who occupies the house is Kingo Gondo, who went from rags to riches in the span of thirty years through his work as a factory owner with National Shoes. His first scene has him dismissing his executives’ advice that they make the shoes less durable and more fashionable, suggesting that it will increase profits. After Gondo excuses the men from his apartment, he gets a call: his son has been kidnapped and held for ransom.

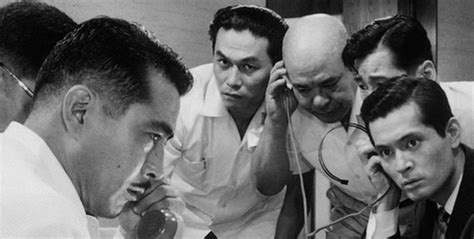

However, it soon turns out that it’s not his son that’s been kidnapped, but his chaffeur’s son, who looks near identical. But when the police arrive, all the drapes in the big house are drawn, and Gondo’s house becomes a prison. After an exchange his made, the film switches genres from a psychological portrayal of the toll of wealth to a police procedural, where the police are competent and all the more determined to bring the extortionist to justice. But where does this motivation come from, and who is it directed towards?

Instead of sympathizing with the father of the kidnapped child, who comes from a lesser background, the police and media put all their sympathy behinds Gondo, who relinquishes his multimillionaire fortune for the ransom. This is not without consequence, as Gondo must release all the wealth he’s accumulated and sell his possessions to restart a comfortable life for him and his family. But as he’s negotiating his next steps with the police, Kurosawa’s mise-en-scéne positions the grieving chauffeur in the background. Even when he’s begging on his knees, the police and Mr. Gondo seem almost oblivious to his presence. In this newly modernized Japan, where upward mobility seems more accessible than ever, more sympathy is given to those with wealth, rather than those who have little to nothing at all.

What’s interesting about High and Low is how a gaze is reinterpreted to question who we should be sympathizing towards. While Gondo is a victim for having to give up his money, there’s also shots that epitomize just how unequal 1960s Japan is. The police’s investigation is critical and efficient, with each department uncovering a new side to the story. But this objectiveness obscures the mindset of the extortionist, whom we see in a couple of scenes glower at the house. As he surveys Gondo’s house, we are positioned in an uncomfortable situation. He walks right by the police as they investigate phone booths, and no one bats an eye. He does not look out of place. And that makes him all the more easy to pass undetected.

As the police investigate further, they must also dive into the more unsavory parts of Japan that the country would like to ignore, like the heroin dens where addicts move about in a zombie-like fashion. It’s one of the most eerie scenes in the entire film. While the Gondo house is mostly stale with the kids providing some life, the dope alley feels translucent. Everyone is a shadow of themself. It’s frightening uncomfortable to see them flock towards the extortionist as he stalks down the alley looking for drugs. Even though he looks out of place, as the similarly dressed undercover cops are pushed away, he is familiar to them. The fact he disturbs the picture of who belongs in certain sections of Japan speaks volumes at how socioeconomic inequality disrupts our perception of humanity.

All the while, the chauffeur stalks the streets with his son, driving him to recollect the memories of what happened while he was kidnapped. The police encourage him to stop playing detective, but it’s almost like the chauffeur is in a completely different film than the rest of the characters. He is not a detective; he is a father desperate for his son’s kidnapper to face justice. He is the overlooked character, and feels as though he must take matters into his own hands.

When someone is kidnapped, it is common for the police to say they will search “high and low” for the hostage. But it’s disparaging sometimes to see the media focus more attention on the plight of the “high” rather than the plight of the “low” in these situations. When the police are giving information to journalists about the development of the case, the journalists in the room suggest it might be beneficial to ramp up the pressure on National Shoes to encourage the board of directors to keep Gondo as a part of the team. Like Kurosawa’s previous Scandal (1950), the media are not ones to be trusted in situations like this. They are vampires in a city full of satiable beasts.

Ultimately, High and Low challenges our gaze. It questions why certain people deserve more sympathy based on their social status, rather than others who languish on a daily basis. While Gondo has earned his money through hard work and is desperate not to lose his fortune, the chauffeur is desperate to earn some vigilante justice when he feels the police are not doing enough. Gondo’s house is comfortable, but presents an uncomfortable symbol for those below. And when you look below, you might not like what you see. It might even frighten you. But, as Kurosawa argues, we should be frightened.

Leave a comment