This barebones documentary, filmed while Jafar Panahi was banned from making films by the Iranian government, is a testament to what one can do with limited resources and strict censorship.

I have a sympathy for censored artists. Everyone hears about banned books all year-round, but it’s another thing entirely to censor films and the artists that make them. There’s an entire generation of film that can be erased due to nationally mandated codes that ascribe to be about protecting national images and moral values. So after I watched The Mirror (1997), I knew I needed to know more about Jafar Panahi. I was intrigued not just due to his style of filmmaking, but also due to how he used the censorship against him to his advantage.

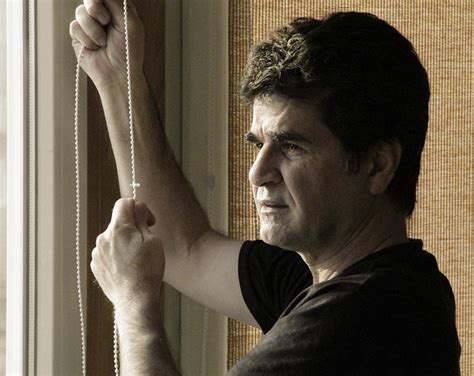

This documentary was made under truly extraordinary circumstances. After Jafar Panahi was handed a 6-year prison sentence and a 20-year ban from filmmaking for his support of Iran’s opposition party, the director found himself under house arrest, waiting to appeal. Armed with only an iPhone and the dutiful coverage of co-director Mojtaba Mirtahmasb, Panahi sets out to record his daily life, while also ruminating on what it means to be a filmmaker under an authoritarian regime.

This film isn’t the easiest watch. Not just because of any graphic content, but also because of its slow pace, which works in the film’s favor. As Panahi reflects what it means to be a filmmaker, I was thinking about what it could possibly be like to be placed under government-ordered house arrest. It’s not like the COVID-19 pandemic where everyone was stuck inside to reduce spreading the infection. Panahi’s stuck inside his house because he will further lose his freedom if he does. He spends a large portion of the film not doing anything, often losing interest in one subject soon after he starts. It’s one of the best uses of creativity-induced depression I’ve seen onscreen.

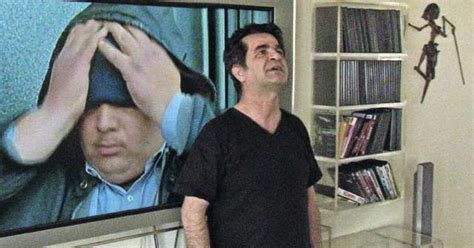

There’s also a great irony in how Panahi uses his quarantine to his advantage. The Iranian government took his ability to shoot with a film crew like he used for The Mirror (1997), but he still has an iPhone, support from friends and family (and Igi, his pet Komodo Dragon), and more importantly, a script for a film that never made it pass the censors. Since he can’t film anyways, why not film the unfilmable?

I appreciated how Panahi doesn’t hide his dissatisfaction with his arrangements. It’s easy to tell someone to keep their head up high when they’re undergoing hardship, but it’s another thing entirely to experience it. We’re given shots that remind us there is a world outside of Panahi’s apartment that he desperately wants to be a part of. There’s a giant crane that sways dangerously close to his balcony. One can hear banned fireworks popping outside. One can hear his neighbor’s incessant dogs barking as Panahi answers the door. While he’s in close contact with his friends and family, the rest of the world is moving on, unaware he’s trying to participate as meaningfully as he can to his society.

Panahi’s comments on his own films stand out. We’re given a look at his rich DVD collection, and his wide-eyed expression as he flips through a main menu. His adoration for the medium of film is evident, as is his dedication to continue that love under house arrest. The script that never was also plays a key role. You can see the eerie foreshadowing that Panahi displays on his face as he reads the story. He didn’t intend for the meaning to sour, but it has. Before, he was writing about a prisoner, and now he is one, forced to look out his window and live through the eyes of someone else.

Like the previous Jafar Panahi film I covered, it’s hard to nail down how one should describe this film after watching it. It’s unexpectedly funny, which is miraculous for a film that deals with depressing subject matter as censorship. But it’s also quite poignant in how it manages to squeeze out small victories out of the mundane. Panahi might be under house arrest, but he’s also determined to keep fighting in the best way he knows how–by creating art that resonates with people.

FURTHER THOUGHTS

- Apparently, this film was smuggled in on a flash drive to get a last-minute inclusion in Cannes. Badass.

- The last shot of this film will linger with you for a long time.

- Jafar Panahi is still planning on going back to Iran to support the protests even after having a warrant out for his arrest, and if you’re surprised by this, you need to see this.

Leave a comment